Imagine: you are seven months pregnant and due for your prenatal check-up, but the nearest health centre is 18 kilometres away. With very little money to pay for travel, you have no choice but to walk. When you finally arrive, you are told to join others waiting for care in an overcrowded waiting room. Eventually, you are able to secure an appointment, but the nurse is attending to two other women at the same time. You notice that one of them is in labour. The nurse is overworked and short-tempered, and you can hear harsh words being spoken to the woman giving birth. Once your check-up is done, you make the difficult trek back home. After this experience, would you return to that health centre to give birth to your child?

This is the reality facing many expectant mothers in Tanzania, where CAGH leads health systems strengthening activities on two projects aimed at improving the health of mothers and their children: Enhancing Nutrition Services to Improve Maternal, Newborn and Child Health in Africa and Asia (ENRICH) Project in Shinyanga and Singida regions, and the Tabora Maternal and Newborn Health Initiative (TAMANI) in Tabora region.

Women may be reluctant to go to a health centre due to issues with access and poor quality of health services. Health care workers in rural facilities, like the nurse in our story, must fulfill a vast range of health needs with limited resources and often inadequate training, diminishing quality of care. Decent infrastructure and readily available medicines can only go so far in improving health outcomes. Health workers are central to the realization of the right to health, connecting communities and the health systems that serve them.

What is health systems strengthening?

A health system is the collection of people, institutions and resources that come together to meet the health needs of a population. Meeting the health needs of a population is not only about having health services available so people can access health care when they need it, but about the mechanisms that are put in place to ensure good health and health for all:

Adapted from the WHO Framework for Health Systems.

These “building blocks” provide the basis for access to and quality of care. Strong health systems enact policies, regulations, and standards to promote people’s well-being. Strong health systems ensure availability and equitable distribution of care, and support empowerment of the most vulnerable members of society. Health systems strengthening encompasses the strategies and responses that improve a health system’s ability to meet the needs of the populations it serves.

The World Health Organization recently identified chronic under-investment in the networks that defend good health as an urgent global health challenge for the next decade. Improving the quality of maternal and child health services cannot be achieved through the work of service providers alone, and needs to involve health systems as a whole. Inclusion of health systems strengthening activities across global health initiatives can advance the sustainability of their life-saving impact, and is needed now more than ever. These are all reasons why CAGH is committed to strengthening health systems globally.

What is CAGH doing to strengthen health systems?

In Tanzania, CAGH works directly with regional and district health managers, and front line health care workers to bridge the gap between national policy and community-level interventions in maternal and child health, with the aim of improving quality and gender-responsiveness of care.

Our approach focusses on:

- Strengthening health systems governance by building managerial and administrative capacity at the individual and organization level with an emphasis on Supportive Supervision as a tool to ensure effective cascade of skills and knowledge;

- Enhancing health information systems; and

- Supporting local health authorities and facility staff in making better use of local data to plan, budget, and deliver services to pregnant women, mothers, and their children.

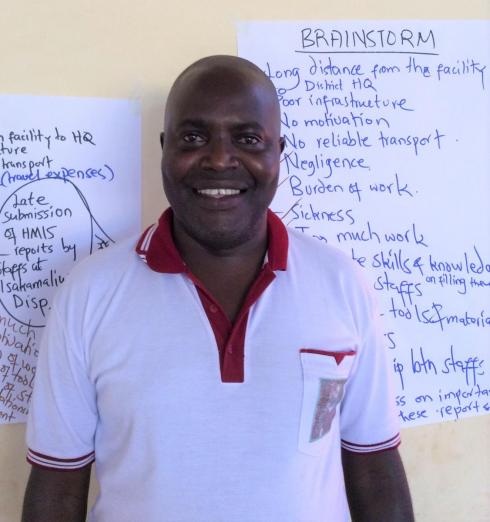

Good supervision of health workers improves health outcomes for the people who use their services. Supportive Supervision calls on managers to lead by listening to staff, and in turn, inspire staff commitment to improving quality of care. Asimwe Tesha Kitingo, District Nursing Officer in Nzega, Tabora Region, says that the skills she and her colleagues have acquired during CAGH’s workshops will “produce better outcomes through improved ways of providing treatment and care.” She says, “the benefit goes to our patients when we practice continuous quality improvement.”

Asimwe Tesha Kitingo Dr. George Mglega

Dr. George Mglega, Deputy Medical Officer for Nzega’s Council Health Management Team says health care managers have busy jobs – it is easy to fall into the trap of doing things the way they have always been done, even if they aren’t the most effective. “After [CAGH’s] training, my team can see a window of change. It has given people some concrete tools to develop new ways of doing things that can be adapted to the working environment in health facilities. Change that leads to improvement is possible!”